Introducing Spark 1 Pro and Spark 1 Mini models in /agent. Try it now →

Blog

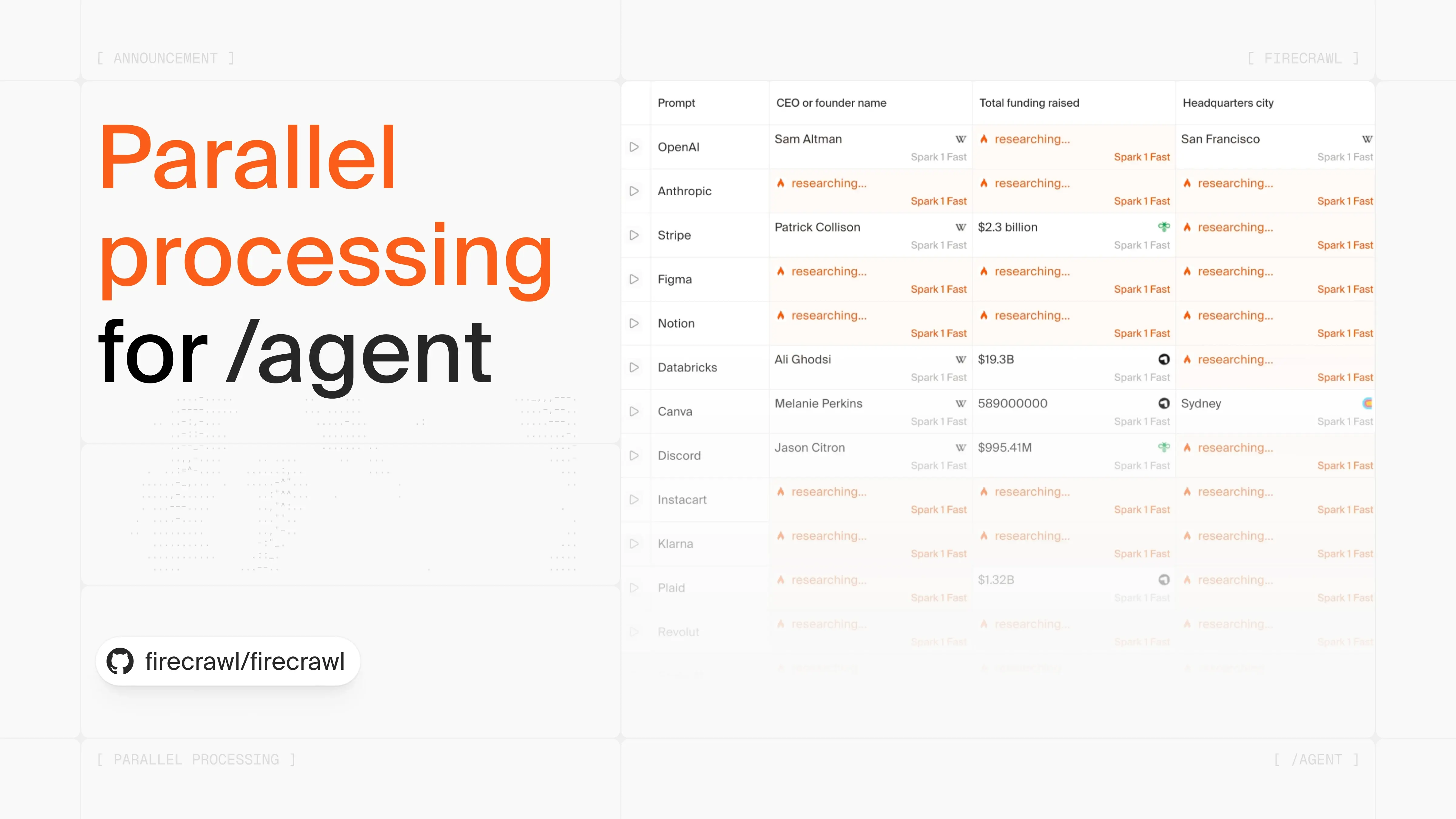

Extract Web Data at Scale With Parallel Agents

Parallel Agents let you batch process hundreds or thousands of /agent queries in a spreadsheet or JSON format with real-time streaming results.

Eric Ciarla

Jan 30, 2026

Introducing the Firecrawl Skill and CLI - Give Agents Real-Time Web Data

A single command teaches AI agents how to scrape, search, crawl, and map the web. Works with Claude Code, Codex, Gemini CLI, OpenCode, and more.

Eric Ciarla

Jan 27, 2026

How Credal Extracts 6M+ URLs Monthly to Power Production AI Agents

How Credal uses Firecrawl to deliver reliable web scraping at scale for enterprise AI agents that need both fresh external context and durable knowledge base ingestion.

Eric Ciarla

Jan 26, 2026

Introducing Spark 1 Pro and Spark 1 Mini

Spark 1 Pro and Spark 1 Mini bring flexible model selection to /agent. Mini is 60% cheaper for everyday tasks, Pro delivers maximum accuracy for complex extraction.

Eric Ciarla

Jan 14, 2026

Introducing /agent: Gather Data Wherever It Lives on the Web

Firecrawl /agent searches, navigates, and gathers complex websites to find data in hard-to-reach places. What takes humans hours, Agent does in minutes.

Eric Ciarla

Dec 18, 2025

Firecrawl + Lovable - Build Web Data Apps Without Writing Code

With the new Firecrawl + Loveable integration, build apps that scrape, search, and interact with live web data - just by describing what you want in plain English.

Nicolas Camara

Dec 16, 2025

Retell’s AI phone agents get LLM-ready content from Firecrawl

How Retell keeps AI phone agents answering from live, LLM-ready content using Firecrawl’s web scraping API.

Eric Ciarla

Dec 04, 2025

Introducing Firecrawl v2.5 - The World's Best Web Data API

Firecrawl v2.5 delivers the highest quality and most comprehensive web data available, powered by our new Semantic Index and custom browser stack.

Eric Ciarla

Oct 30, 2025

We just raised our Series A and shipped /v2

How we got here. What we're building. Why the web's knowledge should be on tap for AI.

Caleb Peffer

Aug 19, 2025

How Engage Together Uses Firecrawl to Map Anti-Trafficking Resources

Discover how Engage Together leverages Firecrawl’s /extract API to collect and organize critical data on anti-trafficking programs and resources across communities.

Ashleigh Chapman

Aug 17, 2025

Dub Builds AI Affiliate Pages with Firecrawl

Discover how Dub uses Firecrawl to power their AI page builder, transforming company websites into affiliate program landing pages in seconds.

Steven Tey

Aug 13, 2025

Zapier Empowers Chatbots with Firecrawl

Discover how Zapier uses Firecrawl to empower customers with custom knowledge in their chatbots.

Andrew Gardner

Jul 21, 2025

Open Researcher, our AI Agent That Uses Firecrawl Tools During Research

We built a research agent using Anthropic's interleaved thinking and Firecrawl. No orchestration needed.

Eric Ciarla

Jul 01, 2025

How Answer HQ Powers AI Customer Support with Firecrawl

Discover how Answer HQ uses Firecrawl to help small businesses import their website data and build intelligent support assistants.

Jacky Liang

Jun 05, 2025

Announcing /search: Discover and scrape the web with one API call

Search the web and get LLM-ready page content for each result in one simple API call. Perfect for agents, devs, and anyone who needs web data fast.

Eric Ciarla

Jun 03, 2025

Introducing Templates: Ready to use Firecrawl examples

A library of reusable playground setups, code snippets, and repos to help you quickly implement Firecrawl for any use case.

Eric Ciarla

May 13, 2025

How Botpress Enhances Knowledge Base Creation with Firecrawl

Discover how Botpress uses Firecrawl to streamline knowledge base population and improve user experience.

Michael Masson

Apr 21, 2025

Integrations Day: Launch Week III - Day 7

Firecrawl now connects with over 20 platforms including Discord, Make, Langflow, and more. Discover what's new on Integration Day.

Eric Ciarla

Apr 20, 2025

Firecrawl MCP Upgrades: Launch Week III - Day 6

Major updates to the Firecrawl MCP server, now with FIRE-1 support and Server-Sent Events for faster, easier web data access.

Eric Ciarla

Apr 19, 2025

Developer Day: Launch Week III - Day 5

Launch Week III Day 5 is all about developers. We're shipping big improvements to our Python and Rust SDKs, plus a new dark theme for your favorite code editors.

Eric Ciarla

Apr 18, 2025

Announcing LLMstxt.new: Launch Week III - Day 4

Turn any website into a clean, LLM-ready text file in seconds with llmstxt.new — powered by Firecrawl.

Eric Ciarla

Apr 17, 2025

Introducing /extract v2: Launch Week III - Day 3

Firecrawl's updated /extract v2 endpoint brings powerful new capabilities like pagination, intelligent interaction via FIRE-1, and built-in search—dramatically improving data extraction workflows.

Eric Ciarla

Apr 16, 2025

Announcing FIRE-1, Our Web Action Agent: Launch Week III - Day 2

Firecrawl's new FIRE-1 AI Agent enhances web scraping capabilities by intelligently navigating and interacting with web pages.

Eric Ciarla

Apr 15, 2025

Introducing Change Tracking: Launch Week III - Day 1

Firecrawl's enhanced Change Tracking feature now provides detailed insights into webpage updates, including diffs and structured data comparisons.

Eric Ciarla

Apr 14, 2025

Firecrawl Editor Theme: Launch Week III - Day 0

Our official Firecrawl Editor Theme provides a clean, focused coding experience optimized for everyone.

Eric Ciarla

Apr 13, 2025

Announcing Deep Research API

Firecrawl's new Deep Research API enables autonomous, AI-powered web research on any topic.

Nicolas Camara

Mar 27, 2025

How Replit Uses Firecrawl to Power Replit Agent

Discover how Replit leverages Firecrawl to keep Replit Agent up to date with the latest API documentation and web content.

Zhen Li

Feb 17, 2025

Introducing /extract: Get structured web data with just a prompt

Our new /extract endpoint harnesses AI to turn any website into structured data for your applications seamlessly.

Eric Ciarla

Jan 20, 2025

How Stack AI Uses Firecrawl to Power AI Agents

Discover how Stack AI leverages Firecrawl to seamlessly feed agentic AI workflows with high-quality web data.

Jonathan Kleiman

Jan 03, 2025

How Cargo Empowers GTM Teams with Firecrawl

See how Cargo uses Firecrawl to instantly analyze webpage content and power Go-To-Market workflows for their users.

Tariq Minhas

Dec 06, 2024

Launch Week II Recap

Recapping all the exciting announcements from Firecrawl's second Launch Week.

Eric Ciarla

Nov 04, 2024

Launch Week II - Day 7: Introducing Faster Markdown Parsing

Our new HTML to Markdown parser is 4x faster, more reliable, and produces cleaner Markdown, built from the ground up for speed and performance.

Eric Ciarla

Nov 03, 2024

Launch Week II - Day 6: Announcing Mobile Scraping and Screenshots

Interact with sites as if from a mobile device using Firecrawl's new mobile device emulation.

Eric Ciarla

Nov 02, 2024

Launch Week II - Day 5: Announcing New Actions

Capture page content at any point and wait for specific elements with our new Scrape and Wait for Selector actions.

Eric Ciarla

Nov 01, 2024

Launch Week II - Day 4: Advanced iframe Scraping

We are thrilled to announce comprehensive iframe scraping support in Firecrawl, enabling seamless handling of nested iframes, dynamically loaded content, and cross-origin frames.

Eric Ciarla

Oct 31, 2024

Launch Week II - Day 3: Announcing Credit Packs

Easily top up your plan with Credit Packs to keep your web scraping projects running smoothly. Plus, manage your credits effortlessly with our new Auto Recharge feature.

Eric Ciarla

Oct 30, 2024

Launch Week II - Day 2: Introducing Location and Language Settings

Specify country and preferred languages to get relevant localized content, enhancing your web scraping results with region-specific data.

Eric Ciarla

Oct 29, 2024

Launch Week II - Day 1: Announcing the Batch Scrape Endpoint

Our new Batch Scrape endpoint lets you scrape multiple URLs simultaneously, making bulk data collection faster and more efficient.

Eric Ciarla

Oct 28, 2024

Handling 300k requests per day: an adventure in scaling

Putting out fires was taking up all our time, and we had to scale fast. This is how we did it.

Gergő Móricz (mogery)

Sep 13, 2024

How Athena Intelligence Empowers Enterprise Analysts with Firecrawl

Discover how Athena Intelligence leverages Firecrawl to fuel its AI-native analytics platform for enterprise analysts.

Ben Reilly

Sep 10, 2024

Launch Week I Recap

A look back at the new features and updates introduced during Firecrawl's inaugural Launch Week.

Eric Ciarla

Sep 02, 2024

Launch Week I / Day 7: Crawl Webhooks (v1)

New /crawl webhook support. Send notifications to your apps during a crawl.

Nicolas Camara

Sep 01, 2024

Launch Week I / Day 6: LLM Extract (v1)

Extract structured data from your web pages using the extract format in /scrape.

Nicolas Camara

Aug 31, 2024

Launch Week I / Day 5: Real-Time Crawling with WebSockets

Our new WebSocket-based method for real-time data extraction and monitoring.

Eric Ciarla

Aug 30, 2024

Launch Week I / Day 4: Announcing Firecrawl /v1

Our biggest release yet - v1, a more reliable and developer-friendly API for seamless web data gathering.

Eric Ciarla

Aug 29, 2024

Launch Week I / Day 3: Introducing the Map Endpoint

Our new Map endpoint enables lightning-fast website mapping for enhanced web scraping projects.

Eric Ciarla

Aug 28, 2024

Launch Week I / Day 2: 2x Rate Limits

Firecrawl doubles rate limits across all plans, supercharging your web scraping capabilities.

Eric Ciarla

Aug 27, 2024

Launch Week I / Day 1: Introducing Teams

Our new Teams feature, enabling seamless collaboration on web scraping projects.

Eric Ciarla

Aug 26, 2024

How Gamma Supercharges Onboarding with Firecrawl

See how Gamma uses Firecrawl to instantly generate websites and presentations to 20+ million users.

Jon Noronha

Aug 08, 2024

Announcing Fire Engine for Firecrawl

The most scalable, reliable, and fast way to get web data for Firecrawl.

Eric Ciarla

Aug 06, 2024

Firecrawl July 2024 Updates

Discover the latest features, integrations, and improvements in Firecrawl for July 2024.

Eric Ciarla

Jul 31, 2024

Firecrawl June 2024 Updates

Discover the latest features, integrations, and improvements in Firecrawl for June 2024.

Nicolas Camara

Jun 30, 2024

FOOTER

The easiest way to extract

data from the web

data from the web

. .

.. ..+

.:.

.. .. .::

+.. ..: :.

.:..::. .. ..

.--:::. .. ... .:. ..

.. .:+=-::.:. . ...-.::. ..

::.... .:--+::..: ......:+....:. :.. ..

....... ::-=:::: ..:-:-...: .--..:: .........

.. . . . ..::-:-.. .-+-:::.. ...::::. .: ...::.:..

. -... ....: . . .--=+-::. :-=-:.... . .:..:: .:---:::::-::....

..::........::=..... ...:-.. .:-=--+=-:. ..--:..=::.... . .:.. ..:---::::---=:::..:...

..........::::.:::::::-::.-.. ...::--==:. ..-::-+==-:... .-::....... ..--:. ..:=+==.---=-+-:::::::-..

. .....::......:: ::::-::.---=+-:..::-+==++X=-:. ..:-::-=-== ---.. .:.--::.. .:-==::=--X==-----====--::+:::+...

..-....-:..::-::=-=-:-::--===++=-==-----== X+=-:.::-==----+==+XX+=-::.:+--==--::. .:-+X=----+X=-=------===--::-:...:. ....

....::::...:-:-==+++=++==+++XX++==++--+-+==++++=-===+=---:-==+X:XXX+=-:-=-==++=-:. .:-=+=- -=X+X+===+---==--==--:..::...+....+

..:::---.::.---=+==XXXXXXXX+XX++==++===--+===:+X+====+=--::--=+XXXXXXX+==++==+XX+=: ::::--=+++X++X+XXXX+=----==++.+=--::+::::+. ::.=...

.:::-==-------=X+++XXXXXXXXXXX++==++.==-==-:-==+X++==+=-=--=++++X++:X:X+++X+-+X X+=---=-==+=+++XXXXX+XX=+=--=X++XXX==---::-+-::::.:..-..